Praise for The Wild Swimmer of Kintail:

I am now 75 pages into your brilliantly written book, I feel like I am walking both back in time with my mum also with you now! I look forward to reading the rest of the book.

Lesley Hampshire, the daughter of Brenda G. Macrow.

Hi Kellan. I’m enjoying reading your book. I hope it sells well. The idea is brilliant. Your descriptions of the landscape remind me of your first book, Caleb’s List. How you remember and know all these Gaelic names! You call a spade a spade. So much in it so you can’t rush through it like a novel. Some really sad bits too. Glad you didn’t freeze to death in the icy waters. I’m going to pass it on to a wild swimmer when I’m finished.

Morag Marshall, Programme Co-ordinator, Colinton Literary Society, Edinburgh.

The Wild Swimmer of Kintail makes you want to run into the water and watch the sunset. Brenda G Macrow lived through World War Two. I lived through Covid and Lockdown. I identified with Brenda G Macrow running away from London to the Scottish Highlands to escape and find herself again. A great book by a beautiful man.

Andy JD, Scotland

Stravaiger reviews The Wild Swimmer of Kintail:

In his recently published third book The Wild Swimmer of Kintail (Rymour Books 2022) Kellan MacInnes returns to explore again the terrain he investigated previously in his first book Caleb’s List (Luath Press 2013.) In between writing those two books MacInnes embarked upon a sortie into fiction in The Making of Mickey Bell (Sandstone Press 2016) while still sticking with his favourite subject: his passion for the Scottish mountains.

In The Wild Swimmer of Kintail MacInnes returns to some of the themes of his previous books; his remarkable survival of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, his life experiences from childhood to the present and his affection for a series of much-loved dogs.

In the halcyon years following his recovery from HIV/AIDS (albeit whilst continuing to have to take formidable daily doses of medication) MacInnes embarked on exploring the Scottish mountains, initially with friends – by no means all of whom were ‘serious’ mountaineers. But subsequently with more committed ‘Munro baggers’, including his mother, who ‘compleated’ her Munros (the Scottish peaks over 3,000 feet) at the age of 61 and went on to climb another hundred Corbetts (the Scottish mountains over 2,500 feet.)

As the years passed and treatments improved, MacInnes was able to return to work; first as a volunteer befriender and fundraiser for one of Scotland’s leading HIV charities, then later as a painter and decorator, a life coach, a bike tour guide, an Airbnb host and a supermarket delivery driver.

In The Wild Swimmer of Kintail the reader’s first introduction, unexpectedly, is not to MacInnes, but to an anonymous young woman who, in the brief prologue to the book, turns out to be ‘the wife of Archie Chisholm, head stalker on the Glen Cannich estate.’ The young woman is on her way to prepare for the arrival of tradesmen, ‘joiners, painters, plasterers and roofers come from Glasgow to get the lodge ready for the gentry’ (a subtle dating of the period.) As she stands, at the spot in the remote and beautiful Glen Cannich, where today: ‘there looms the vast, grey, concrete edifice of the giant Mullardoch mass gravity hydro-electric dam,’ the young woman experiences a haunting premonition.

A few pages later, the reader is introduced to Brenda G. Macrow, the 1940s poet, travel writer, mountaineer and pioneer of wild swimming who inspired MacInnes to write The Wild Swimmer of Kintail. Now this reader, had to her extreme chagrin, paid virtually no attention to the quotations which appear throughout the book, printed in italics, under the heading ‘Macrow 1946’ until well into the latter half of the book.

Then the realisation dawned that the quotations are in effect flashbacks, crucial to the integrity of the book. The quotations tell Macrow’s story (a true, real-life story incidentally) of escaping London at the end of the Second World War, taking the night train to the far north-west of Scotland where, accompanied only by her faithful Skye terrier Jeannie, Macrow embarked on the challenge of wild swimming 28 hill lochans in remote and mountainous Kintail.

And now, 1946 and 2022 are temporarily welded together in the first chapter ‘London’, but only briefly, as MacInnes explains, over dinner in a Hungarian restaurant, the reasons why he has decided to follow in Macrow’s footsteps and take on the challenge of wild swimming the hill lochs of Kintail.

MacInnes’s brief sortie to London over, he heads north, the music of the place names playing in his ears: ‘Inverness, Beauly, Muir of Ord, Conon Bridge, Dingwall, Garve, Loch Luichart, Achanalt, Achnasheen, Achnashellach, Strathcarron, Attadale, Strome Ferry, Duncraig, Plockton, Duirinish and Kyle of Lochlash.’

But alternating, smoothly and uninterruptedly, and this is the triumph of MacInnes’s prose, are his life experiences from childhood into the present. And always, accompanying MacInnes’s life events and reminding the attentive reader, are the flashbacks to the summer of 1946, to the six months Macrow spent in Kintail. Depictions of halcyon life in the north-west Highlands in the 1940s; the welcome granted to hotel visitors, the search for a cosy shepherd’s cottage when cheaper accommodation is needed, the pleasure of cycling ‘steadily,’ as Macrow does, ‘along the shore of Loch Long.’

But the present constantly invades the past. In 1946 an exhausted Macrow is welcomed, with great relief, when after one of her amazing, gruelling treks, she gets back home to Iron Lodge, and is greeted by her landlady Mrs Munro with pots of tea and scones. But when MacInnes and his companion, the rather mysterious ‘L’, have to camp outside the today, derelict Iron Lodge they find it a comfortless and even sinister place.

The reader is ceaselessly and relentlessly reminded of the present: ‘In 1946 this old right of way led from Iron Lodge over to Glen Cannich but today much of the path lies submerged below the waters of the vastly expanded Loch Mullardoch.’

The reader will enjoy the lyrical description of landscape, but will also enjoy the humour of MacInnes’s relentless self-mockery: ‘Oh crikey he’s going on about fence posts now, I hear you say.’

Finally MacInnes reaches the penultimate hill loch on Macrow’s list: ‘In the corrie below Beinn Fhionnlaidh, number 27 on Macrow’s list, my second last hill loch.’

The reader is invited to recall and recollect the past and the present in the final pages in a perfect and profoundly satisfying conclusion, but nevertheless with an acute and poignant sense of loss for so much beauty lost for ever.

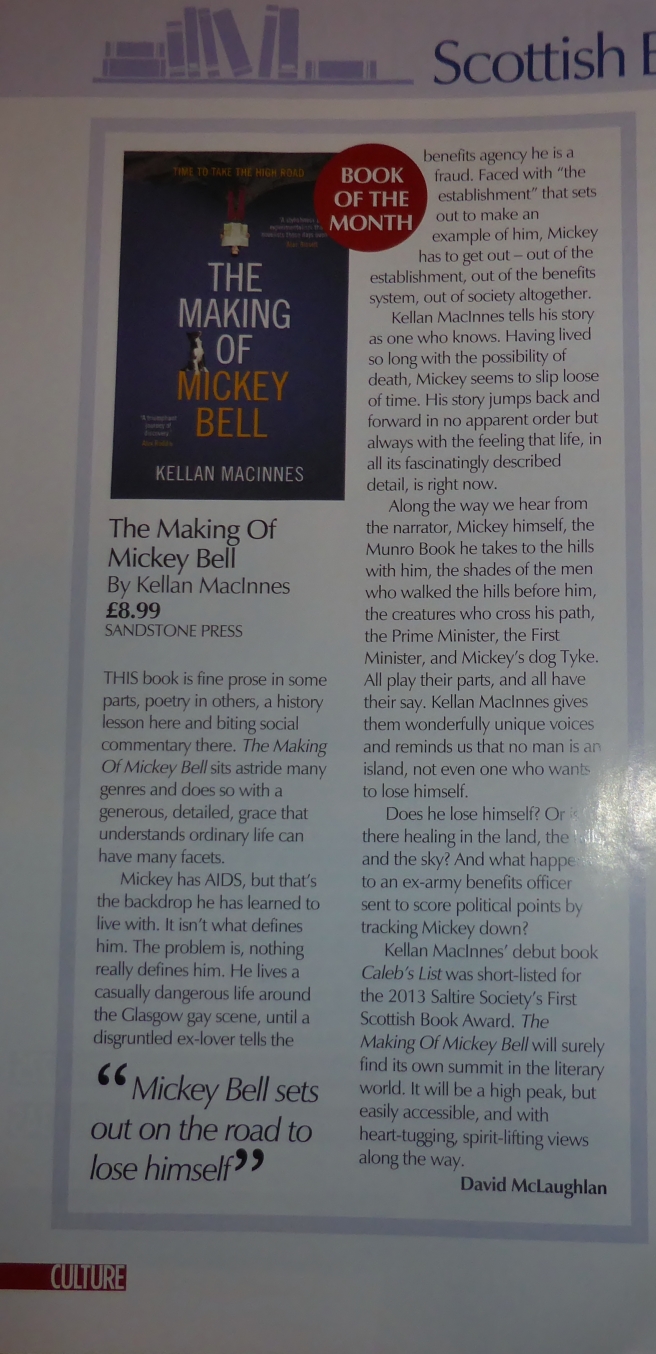

What reviewers said about The Making of Mickey Bell :

The Scots Magazine reviews The Making of Mickey Bell:

‘A Highland road movie , rich in encounters… MacInnes has real talent.’

The Scotsman

‘MacInnes’ first novel… launches a refreshing new talent into the Scottish fiction firmament.’

Scottish Field

‘Stylish and experimental… a life-affirming book that keeps you reading.’

The Courier

‘By turns… hilarious, moving and thought provoking. One of the finest novels of 2016.’

Am Bratach

‘An outstanding book that is both memorable and unique.’

Undiscovered Scotland

“One of the best artistic reactions to post-Referendum Scotland there has been so far… bursting with ideas, stylistic flourishes, unusual narrative voices and literary experimentation.”

Alistair Braidwood @Scots Whay Hae!

‘A fantastic book from the very talented author of Caleb’s List.’

Alex Roddie writer of mountain fiction

Scottish Field reviews the Making of Mickey Bell

MacInnes’ first novel employs an unusual style of writing that launches a refreshing new talent into the Scottish fiction firmament. Jumping from the voice of the narrator to Mickey’s inner monologue, MacInnes leads us away from the rough Glasgow streets to a different kind of rough in the Highalnds with the topical theme of ‘Broken Britain’ thrown into the mix.

Kevin Crowe reviews The Making of Mickey Bell for Am Bratach magazine

Our eponymous hero, a Glaswegian gay man living with HIV who enjoys his booze and cannabis, decides after being beaten up by a queerbasher outside a pub in Lochinver to climb all of Scotland’s Munros (mountains over 3,000 feet). His companion is his loyal if temperamental Collie, called Tyke. At the same time he is being followed by an investigator from the DWP (Department of Work and Pensions) after a former and psychotic boy friend shops him for claiming disability payments he should no longer be entitled to.

In this comic novel which by turns is hilarious, moving and thought provoking and which takes place during 2014’s Independence Referendum we meet a cast of memorable characters worthy of Dickens. These include Maggie, his aunt who lives in Stoer in Assynt where she runs the local post office. Mickey looks after the post office one year while she goes on holiday. It is while living in Stoer he is beaten up by the homophobic, woman abusing drunken mountain guide Dougal Anderson. But don’t worry: two hundred pages later, in one of the most hilarious passages in this at times laugh-out-loud novel, Mickey gets his revenge on Dougal with the help of one of the women the mountain guide stalked: the hippieish Tamara Stricher, owner of the Love Shack, a van with tie-dyed curtains. You’ll have to read the novel to find out just how deliciously appropriate is the revenge.

Then there’s Zelda – a heavy drinking, overweight, middle aged, promiscuous queen – who provides Mickey with a temporary refuge after his friend’s ground floor flat has been trashed by Johnnie, Mickey’s psychotic former boyfriend. Zelda also inherited a caravan in the Highlands, which he has only ever used once after bad experiences with locals and with midges. He lets Mickey use it as a base for some of his climbs. Carmen d’Apostolini is the fierce advocate and welfare rights worker who ensures Mickey gets all the benefits he’s entitled to and who probably puts the fear of God into any civil servant who denies her clients any money.

There is also Mr Fuk Holland 2012, a Dutch gay Hell’s Angel into sadomasochism who spends time each summer with fellow bikers revving along narrow Highland roads. At one point in the story he saves Mickey from the police by acting as a decoy, riding at high speeds along single track roads before being stopped on the A9 near Tore. As he roots for his license, the contents of his pannier trail along the layby, including his various S&M aids, much to the blushing consternation of the young copper.

John Fraser-Smythe is a thinly disguised parody of Iain Duncan Smith, the former Secretary of State for the DWP, here called the DSS (Department for Scroungers and Scivers). Fraser-Smythe wants to make an example of Mickey, partly because he is claiming benefit which in Fraser-Smythe’s view he shouldn’t get, but mainly because Mickey is Scottish and presents an ideal opportunity to poke the eye of Alex Salmond (who also has a walk on part). His weapon in this battle is Nige, a former incompetent and short-lived commando who now works for the DSS. Because of his commando experience and because he once went walking in Scotland, he is tasked with following Mickey. With his government credit card in hand he purchases all sorts of overpriced state of the art equipment which he doesn’t know how to use.

In various pubs, hotels, mountain slopes and other locations we meet an array of other characters who either help or hinder, either accidentally or deliberately, Mickey’s Munro quest. One of these is the Canadian media magnate Sir Gideon George Oliver Brokenshire who owns a vast tract of the Highlands but only visits his estate in order to shoot the wildlife.

There are also all the non-human characters, three of whom speak at various points in the story. There is Fithich, a raven who looks down with disdain on Mickey climbing a ridge the raven can swoop above. There is also Mickey’s dog, Tyke, who has a very different view of the world from that of his master. And finally there is the Munros Book which, at various junctures, whines at Mickey for not listening to it and for not taking the best routes up various mountains.

The narrative is regularly punctuated with statistics on Mickey’s health, in particular his Viral Load (which describes the amount of HIV – human immunodefiecency virus – in an individual’s blood) and CD4 count (which measures the strength of an individual’s immune system).

Like most humour, it is at its heart a serious book. As the Liverpool poet Roger McGough once said: humour is often the best way to be serious. The author clearly knows what he is writing about. He has been living with HIV since the 1990s, was a volunteer for a major Aids charity and has always spent much of his time walking in the mountains. He has used his experiences to write one of the finest novels of 2016.

The Courier reviews The Making of Mickey Bell

Mickey Bell is sick, but not as sick as the dole think he is. Grassed up for benefit fraud by his psychotic ex, Mickey needs to make a sharp exit. And where better to hide than up a Munro? With faithful dog Tyke at his heels, Mickey flees a Glasgow rife with referendum fever for a country where crows and collie dogs can speak. A wicked queen, a gay Hell’s Angel and total disregard for the legal implications of love could be just what Mickey needs to turn his life around.

A stylish and experimental book, this is ultimately a triumphant journey of discovery. Author Kellan MacInnes thinks he contracted the HIV virus in the summer of 1988. Diagnosed with AIDS-related cancer in 1997 he packed in his job, cashed in his pension and went home to die… only he didn’t.

Graphic in places and with language not for the fainthearted, this is a life-affirming book that keeps you reading. Since not dying of AIDS, Kellan has worked as a befriender, a painter and decorator, a supermarket delivery driver and a bike tour guide. His first book Caleb’s List was shortlisted for the 2013 Saltire Society First Scottish Book Award, Scotland’s most prestigious literary prize. He lives in Edinburgh and has been climbing Scotland’s mountains since he was a teenager.

Scottish book of the week: 8/10

Alistair Braidwood @Scots Whay Hae! reviews The Making of Mickey Bell

Kellan MacInnes’ novel, The Making Of Mickey Bell, is darkly comic tale with a protagonist who deals with triumph and despair and treats those impostors as the same…

Kellan MacInnes’ novel, The Making Of Mickey Bell, is a heart-felt missive to Scottish literature, referencing many of its best writers and poets…

Kellan MacInnes’ novel, The Making Of Mickey Bell, is an experimental work at times reminiscent of Kafka and Kelman…

All three of the above were attempts to begin this review, and all of them give a truth, but not the whole truth. The truth is that Kellan MacInnes’ The Making Of Mickey Bell is possibly the most packed novel you will read this year. It’s bursting with ideas, stylistic flourishes, unusual narrative voices and literary experimentation which makes it stand out in the crowd. There is so much going it threatens to overwhelm at times, but, mainly through Mickey Bell’s constant stravaiging, you are moved on to the next scenario slightly dazed but never confused.

It’s a novel which takes urban realism kicking and screaming into the wilds of Scotland. Imagine the famous scene in Trainspotting where Tommy tries to get Renton, Spud and Sick Boy up a mountain, and instead of them turning tail and heading back to Leith they decide to give it a go. Mickey Bell uses climbing Munros as personal therapy, but his embracing of the country is a strong reminder, as if it were needed, that it’s not so “shite being Scottish” after all.

This is an important point. Trainspotting was published in 1993 and was set in the late 1980s, bang in the middle of a Tory hegemony which Scotland didn’t vote for and was powerless to change. It was a time pre-Devolution and Referendum, and as such it remains the perfect novel for its time and place. The Making Of Mickey Bell, by contrast, is one of the best artistic reactions to post-Referendum Scotland there has been so far. Despite the actions and deeds of many whom Mickey meets, this is a novel which ultimately offers hope for the future, both individually and shared.

The titular Mickey Bell is our guide through the novel, meeting a rogues’ gallery of the good, bad and ugly as he goes about his quest to bag all of Scotland’s Munros. He is living with HIV/AIDS which means not only a regime of regular medication, but having to deal with the “labyrinthine” benefits and welfare systems. It’s little wonder he wants to head for the hills.

The rest of MacInnes’ characters, or “Cast” as he prefers it, are an equally unforgettable and unlikely bunch. There is John Paul O’Malley, a buddhist with serious issues, Zelda, a wicked Queen who is not quite Disney friendly, John-Fraser Smythe, the Secretary of State at the DSS who takes a keen interest in Mickey Bell, and Mr Fuk Holland 2012 who is heroic in name, deed and nature. Add to them Tyke, Mickey’s loyal collie dug, and a raven called Fithich, as well as the mysterious and eerie Taghan.

Talking animals appear to be a theme in Scottish fiction in 2016 with James Robertson’s articulate toad in To Be Continued and the argumentative alpacas in Kevin MacNeil’s The Brilliant and Forever, but MacInnes takes this even further with the thoughts and musing of ‘The Munros Book’, a talking book in the most literal sense. It’s another example of the surreal touches which are a feature of The Making Of Mickey Bell, making it such a curious read. Throw in Bette Davis and some other well-kent and no sae well kent faces, and you begin to understand how eccentric and off-kilter the book is.

Homage is paid to Scottish literature, and, as well as rejoicing in the shock and awe-naw of Irvine Welsh and John Niven, there are nods towards Edwin Morgan’s concrete poetry, the hard-hitting socio-political commentary of Duncan McLean, the heart and conscience of James Robertson, the offbeat realism and sensuality of Alan Warner, and the poetic feel for the land of Nan Shepherd. I’m sure when you read it (and you really must read it) you’ll find your own touchstones, but the greatest skill MacInnes shows is in knitting all of these influences together to create something brand-new and unique.

The Making Of Mickey Bell is all of the above and I feel I haven’t even scratched the surface in this review. What is most impressive is the desire to do something different. Actually, it’s the desire to do something different and pull it off. Kellan MacInnes has been willing to experiment with form, structure and language and you can’t help but feel he has had a ball doing it. There is a lust for life, and for writing, which runs through the book, and which keeps you turning the page. I would love to know what Mickey Bell does next, but I’m even more keen to read more Kellan MacInnes.

Allan Massie reviews The Making of Mickey Bell in The Scotsman

Kellan MacInnes’s first book, Caleb’s List, was on the short leet for the Saltire Society’s First Scottish Book Award in 2013. The original list was made by Caleb George Cash in 1899 and detailed all the mountains and big hills that could be seen from the top of Arthur’s Seat. Mountains feature in MacInnes’s new novel, this time Munros.

His hero Mickey Bell is living in squalor in a Glasgow tenement and has been infected with the HIV virus by his pretty but mentally disturbed, perhaps psychotic, boyfriend. His spirits are understandably low, but with the help of a determined and highly organised adviser who knows all the Social Security ropes, he gets a Disability Living Allowance. So far, so good. Meanwhile he also gets himself a dog and, to escape depression, takes to hill-walking. Following a guidebook – instructions recorded in the text with map references supplied, he starts climbing Munros, hoping eventually to have climbed them all. However his petulant and aggrieved ex-boyfriend reports him to the authorities who – not unreasonably, you may think – take a dim view of paying disability benefit to a chap apparently capable of climbing mountains. The author’s opinion seems to be different: the mountain climber is entitled to his disability allowance because the British Government is in the hands of very rich men.

Be that as it may, Mickey takes off to the hills with his faithful –and very engaging – dog, and what we have is a sort of Highland road movie, rich in encounters, some unpleasantly violent, some comic, some touching, a few exhilarating. McInnes is very good at domestic and family scenes. Mickey has a loving auntie who insists that he attends a family wedding and hires a kilt for him. It’s a good scene; he makes a click there too, and the suggestion is that his love-life may eventually run smooth. The story is set against the background of the independence referendum, but MacInnes has nothing new or interesting to say about it. Indeed the referendum is really no more than decoration. There’s a spot of fairly predictable satirical stuff about politics, but it’s drearily conventional.

This is a pity. When the author’s imagination is engaged, and his prejudices laid aside or forgotten, he often writes very well. He has a keen eye for oddity and a sympathy for the diverse characters who cross Mickey’s path. His description of wild country and mountain scenery are precise and vivid, and he conveys his delight in the mountains alluringly. Mickey himself becomes a convincing and in many ways admirable character, certainly more likeable than he seems in the early chapters. One does get the sense that he is on an emotional journey, learning more about himself and making himself into a better man. So the novel carries a message of optimism. One might remark also that the relationship between Mickey and the dog is tenderly and charmingly done. A novel that seems to start out at the school of early James Kelman becomes rather different, as indeed late Kelman is different. His influence is clear, and on the whole good.

Nevertheless there are weaknesses. Scenes repeatedly go on long after they have made their point. MacInnes has little sense of the value of economy, though economy is what this novel cries out for. The structure is ramshackle, but even a picaresque novel, which this to some extent is, benefits from a firm structure. Likewise the different registers jar. The political passages are jejune, in contrast to the felt life of Mickey’s wanderings and his developing maturity. MacInnes may be seeking to convey the gulf between the humanity of the individuals – Mickey and those he meets on his journey – and the indifference, even callousness, of officialdom, but it’s not enough merely to state the latter. Even the devils deserve their own tune.

As a whole, therefore, the novel doesn’t work, lacking coherence. Yet parts are good, even very good. MacInnes has real talent, but at present the talent is unharnessed, and when his imagination is at a low ebb, he slips too comfortably into cliché.

Undiscovered Scotland reviews The Making of Mickey Bell

Go into any Scottish bookshop and you’ll find no shortage of books about the Munros, the 282 individual mountains in Scotland above 3,000ft in height. Generally they fall into two categories: books that show you how to climb the Munros yourself; and books that recount the author’s own adventures on the mountains, whether in winter, or in older age, or as a single expedition, or in other circumstances that help set apart their feat as especially unusual, noteworthy or inspiring. The Munros and their collection has also served as the focus of, or background to, works of fiction.

As a result, you could be forgiven for thinking that just about every angle it’s possible to take on the Munros has been covered, and committed to print. One of the many joys of “The Making of Mickey Bell” by Kellan MacInnes is that it proves beyond doubt that there is always room for a new way of looking at a well-trodden subject, and that it is possible to produce as a result an outstanding book that is both memorable and unique. “The Making of Mickey Bell” is a novel that explores the interaction between a life lived in the darkness and gloom of one of the most disadvantaged corners of a very modern Scotland on the one hand, and the timeless joy of reaching a summit cairn and drinking in a view that stretches for miles on the other.

Mickey Bell is 35 years old. He lives on the ground floor of one of the blocks of high flats in Drumkirk, a fictional suburb of Glasgow. He has been living with HIV for five years, and only surviving because of his medication. For the same amount of time he’s been claiming benefits because his medical condition and complications arising from his medication makes it impossible for him to work. Or, at least, that was what his advocacy worker told the DSS at the time the benefits award was made, and she should have known because she had previously worked for them.

The thing is that Mickey has become inspired by the Munros, and a chance a few years before to spend some time on the west coast of Sutherland allowed him to begin climbing and collecting them, and to acquire his collie dog Tyke. Ever since, Mickey has steadily closed in on his goal of climbing every Munro. But then Mickey’s psychotic ex-boyfriend, Jonnie, reports him to the benefit fraud hotline, and with a decision about to be made on Scotland’s future as an independent nation (or not), the prospect of a high profile conviction of a Munro-bagging benefits scrounger is one that appeals to the very highest levels of the powers-that-be in London.

This is a book that relentlessly picks up pace as it proceeds. Mickey only has a few Munros left to climb, but fears that the DSS are on his tail. Can he complete his goal before they track him down? And if he does, what happens then? “The Making of Mickey Bell” is a lovely book that captures perfectly the atmosphere of remote Highland communities , and the joy of hillwalking. The author’s approach to storytelling has some innovative twists that work beautifully. We see much of the action from Mickey’s point of view, though later we spend some time with Nige, a DSS investigator. Amongst other viewpoints used to tell the story are those of Tyke, the collie, and “The Munro Book”, the book which Mickey found in a charity shop and in which he has ticked off his conquests. The result is a long way from any other book about climbing Munros you are likely to have encountered, not least in that the actual climbing is usually incidental until the very end. Yet it is also likely to be one of the more memorable books about Munros you will have read: or about life in modern Scotland, for that matter.

Alex Roddie reviews The Making of Mickey Bell

Mickey Bell is down on his luck. HIV-positive and unemployed, he feels as if he never really got to make a start in life. This book is all about Mickey and how he overcomes many of his challenges, finding something worth living for – an appreciation for the mountains of Scotland.

Kellan MacInnes’s character creation here really is first class. Mickey is brought to life right from the start, and even minor characters are deftly painted with a skilful blend of humour and sometimes tragic realism. The description’s great too – much of the book is highly evocative of working-class Glasgow, and the narrative builds up a very distinctive picture of the area. When the narrative moves to the mountains, there is a tangible beauty in the description, timelessness perhaps tinged with the ache of longing. This author loves the mountains, and it shows.

The writing style is highly distinctive. It contains direct monologues from Mickey and other characters, which provide a startling and sudden insight into the minds of the people this story is all about. Point of view flits from character to character – but this is more than mere head-hopping. It’s done with deliberation and skill, and helps to create a rich and complex reality for each scene. Sometimes the narrative even takes us inside the mind of a wild animal of the mountain. I can’t think of any other work of fiction that uses multiple POVs this effectively.

If this book has a mission, I’d say it’s for some form of social justice. The champions of The Making of Mickey Bell are the marginalised and the downtrodden. Although it’s arguable that the climax of the story poses more questions than it answers, there is a powerful message of hope here. From a bleak tone in the first pages, things become more optimistic, and Mickey swells with purpose when he discovers the Munros.

This novel is politically opinionated, pro-Scottish independence and anti-establishment. Although it would be easy to say that people with opposing views will find the treatment of these subjects a little blunt and heavy handed, I believe the strength of the characters and the story will overcome any difference of opinion. Just as love of the mountains unites people with disparate political beliefs, so all readers will be able to appreciate Mickey’s triumphant journey of discovery in the outdoors.

This is a fantastic book from the very talented author of Caleb’s List. It’s a story of social injustice, ordinary people trying to find some sense in a desperate world, and the redemptive power of Scotland’s mountains.

What reviewers said about Caleb’s List:

“An acclaimed mountain memoir.”

The Sunday Mail

“A tribute to the healing power of the Scottish landscape and to survival against the odds.”

The Scotsman

“A triumphant debut.”

The Great Outdoors

Joyce MacMillan, journalist and theatre critic

“Caleb’s List is an excellent book. Caleb Cash himself is an important if neglected figure in the history of the Scottish outdoors and the author’s personal story gives the book an emotional power unusual in a guidebook.”

Chris Townsend, author

“This is not just a book about hillwalking and history. At its heart this is powerful landscape writing that explores the strong bond between a person and the hills they love… The author writes with skill and considerable authority.”

Alex Roddie, author

In January 2014 TGO magazine included Caleb’s List in their 8 best outdoor books of 2013.

Review of Caleb’s List from The Scottish Mountaineer:

“This is a delightful book, receiving a welcome publication in paperback.

It’s hard to say in a nutshell what Caleb’s List is. On the surface it’s a guide to climbing 20 Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh. (A much more attractive list of hills than you might imagine.)

But it’s also the story of a Victorian mountaineer, geographer and antiquarian, and the tale the author’s personal struggle with HIV. As well as a compendium of all sorts of interesting facts and history about the hills being climbed.

When this book was first published in 2013 it was shortlisted for the Saltire Society’s Scottish First Book Award, and once you start turning the pages it’s not hard to see why.

This isn’t the sort of guide book you pick up to get the bare bones of your route for the day; this is the sort of book you settle down with for a good read, or dip into from time to time to check a detail and stay for a whole chapter, full of surprises and interest, asides and insights.

The hills covered – MacInnes dubs them The Arthurs – range from Ben Lomond in the west to Lochnagar in the east, with the most distant being Beinn Dearg by Glen Tilt and the closest being East Lomond in Fife. Others include Stob Binnein, Ben More, Ben Vorlich, Ben Lawers and Schiehallion.

This book certainly provides more than adequate details and directions to get you up the hill and down again, but it offers a rambling and far more enjoyable journey than a bare list of directions and distances would offer. I could be picky and say that the reproduction of the maps is quite poor but, to me, that’s a trifling point: you’ll be taking a map anyway, and the picture painted by the words is far richer than the one you’d gain from clearer contours.”

Neil Reid, Editor

The Scottish Mountaineer is a magazine published on behalf of the Mountaineering Council of Scotland, the sport’s representative body.

Review from TGO The Great Outdoors magazine :

“Caleb’s List documents Kellan MacInnes’ journey from discovering (and accepting) that he will have to live with HIV/AIDS for the rest of his life and setting the challenge of climbing twenty mountains visible from the peak of Arthur’s Seat. This is a deep and triumphant authorial debut.”

Review from Scotland Outdoors Magazine

“Partly an inspirational hill-walking account, partly a frank and engaging memoir of life with HIV/AIDS, this unusual and likeable book is based on the Victorian geographer Caleb George Cash’s list of mountains visible from the summit of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh. Panels, maps , drawings and photographs add to the rich mix of anecdote as the author details his walks up Ben Venue, Ben Vorlich, Schiehallion, Lochnagar and the rest.”

Alex Roddie, writer of mountain fiction reviews Caleb’s List:

Caleb’s List by Kellan MacInnes is a story with two equally important threads. Firstly, the author is an HIV/AIDS survivor who found the strength to rebuild his life through a love of hillwalking and the outdoors. Secondly, there is The List … not Munro’s List that every Scottish mountaineer is familiar with, but Caleb’s List of twenty peaks visible from the top of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh (“The Arthurs”). This book is an enchanting and meaningful blend of these stories. As Kellan climbs the peaks on Caleb’s List, we learn about the life of Caleb himself and the deeper truths of the landscape all around.

Caleb Cash was a mountaineer who lived in Edinburgh at the end of the 19th century and start of the 20th. Unlike the upper middle class climbers of the era who had ample leisure time and funds at their disposal, Caleb was a humble geography teacher and therefore his mountaineering exploits tended to be less ambitious. Nevertheless, he was a true lover of the Scottish landscape and an early champion for environmental conservation. Caleb is vividly brought to life and I found it tremendously refreshing for a Scottish mountaineering book to focus on one of the unknown pioneers of the sport. For example, although I am a dedicated student of the history of climbing, I had no idea that Caleb Cash had explored the Cairngorms years before the Scottish Mountaineering Club. He was also a ‘keen but appreciative critic’ of the Ordnance Survey and pointed out manyinaccuracies in the early maps of the Highlands. This man may not be remembered as universally as Sir Hugh Munro, but he certainly made his mark.

The wider historical and cultural context is also explored in a very engaging way, not only in the text itself, but also in the frequent illustrations and diagrams. The author is fascinated by the earliest history of exploration in the Scottish hills. The author takes us back to the Little Ice Age when the mountains were capped with ice throughout the summer. Early mapping, road-building, scientific experiments, and shieling life are all here.

But this is not just a book about hillwalking and history. At its heart this is powerful landscape writing that explores the strong bond between a person and the hills they love. Nature is also a key theme. I detected a clear link to Robert MacFarlane’s work, which is really the greatest praise I can give this book; it makes you smell and taste the Highlands.

The author writes with skill and considerable authority. Not only has he climbed every peak on the list (some of them many times during his extensive hillwalking career), he has also made it his business to learn everything that can possibly be learned about Caleb Cash and his world.

If the book has any fault, I would say it does not focus enough on Kellan’s own extraordinary journey, which is itself an inspiration. However is not enough to detract from the 5* rating I believe this book wholeheartedly deserves.

This is not a ‘ripping yarn’ about mountaineering catastrophe; it doesn’t feature celebrity climbers, the highest peaks or the hardest climbs; and it certainly is not about breaking records or doing any of the things that commonly make it into contemporary mountaineering books. However, in a quiet, unassuming, and utterly enchanting way, this is one of the best books on the Scottish Highlands I have read in a long time.

Fraser Gold, Milngavie Mountaineering Club reviews Caleb’s List :

Compelling reading which I found hard to put down.

Twenty hills visible from Arthur’s Seat were listed by Caleb Cash over 100 years ago. This book revisits the listed hills, some using public transport as Caleb would have done. Walks are described in detail, with natural history, geological, historical and archaeological information very deftly interwoven and illustrated. The quality of writing creates vivid pictures and makes the reader feel the experience of treading the routes.

Separate chapters give due credit to Caleb’s almost forgotten contribution to Geographical studies in Scotland, including the recognition and rescue of the historic Pont maps. It made me relive outings on the hills mentioned, and made me want to go back and appreciate the intimate beauties and the views more fully. Place names are given fair and detailed explanation and the correct Gaelic spellings suggested with very good guides to correct pronunciation. There is a very full bibliography.

The almost poetic power of the text at times must owe much to the author’s experience of doing the hills and writing the book whilst living with the aftermath of an illness which had been diagnosed as imminently life threatening.

In my very short list of best mountain books.

Chris Highcock author of Hill Fit reviews Caleb’s List:

This book is many things: biography, autobiography, guidebook and historical/geographical commentary. It is the story of two men: Caleb Cash a Victorian mountaineer who among many other things, drew up a list of the hills visible in the panorama from Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, and Kellan MacInnes the author who found the list and decided to climb those hills. His climbs power his reaction to an illness.

There is a third character too: the Scottish countryside. The book is rich with a love for the hills, people, history and language of Scotland. Reading it I realised I’d climbed all but 2 of these hills and today using it as a guide I followed this book’s directions for one of the hills. The route description is very accurate and as I walked the landscape came alive with the stories told by the author.

Highly recommended if you love the hills or even if you don’t : the story of all three characters: Cash, MacInnes and the mountains is complex and fascinating.

Liz Marshall, hillwalker reviews Caleb’s List:

In 1898, Caleb Cash an unsung Victorian hero with many interests drew up a list of the 20 hills visible from the summit of Arthur’s Seat. Caleb’s list (hence the title of the book) of Scottish hills provides the backdrop to this beautifully written and meticulously researched book. MacInnes has wittily named these hills as the Arthur’s and his book provides an informative and entertaining guide to climbing these Arthurs.

The description of theroutes are clear and concise with plenty of detail to assist the navigationally inexperienced. Useful details such as public transport, advice for dog walkers and restorative tea shops make the planning easier. Each of the 20 hills have their own chapter the flowers and fauna and landscapes of each hill are beautifully described with little illustrations. MacInnes’ knowledge of folklore, geology and history gives each hill its own unique feel. It’s also fun to know who “owns” these hills and MacInnes provides details about this too.

But Caleb’s List is much more than a guide book. MacInnes has a deep love and knowledge of Scotland and her mountains but he also has a very personal story to tell. Although briefly touched on, MacInnes’ own story and his mental climb to fitness and happiness is very moving. The restitutional power of the land and the wild places and MacInnes battle for health are beautifully described.

Caleb Cash – teacher and environmentalist is also vividly portrayed through Caleb’s List. A Victorian with purpose and vision he too loved the wild places and the wild life of Scotland and MacInnes also tells Caleb’s story as he takes us on his tour of the hills.

I loved this book. If you need some inspiration to get your boots on and get walking, take some inspiration from Caleb and MacInnes – and get walking.

Stravaiger, a compleat Munroist reviews Caleb’s List:

Yet another guide to Scotland’s mountains to add to the lengthy rows of such books to be found on the shelves of our bookshops? No. Caleb’s List is altogether different as its title might suggest.

So who on earth was Caleb, and what did he list? Caleb George Cash taught geography and music at the Edinburgh Academy for 30 years. But this august educational establishment was not where his teaching career began. Born in Birmingham in 1857, into a working class family, he studied hard at school, eventually becoming a student teacher and then a fully fledged teacher in the school in which he’d once been a pupil. So the move north to Edinburgh, to the Academy, and to a home with his wife Alice in genteel Comely Bank was a big step up in the world.

Caleb Cash became a fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in the 1890s. He was also a pioneer of Scottish mountaineering and one of the generation of list makers, which included such luminaries as Hugh Munro, John Rooke Corbett and much later Fiona Graham.

Kellan MacInnes, browsing in his local public library, close to his home below the slopes of Arthur’s Seat, came across Caleb Cash’s list of 20 Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat. MacInnes set himself the challenge of climbing the hills on Caleb’s list and in doing so the idea of writing a book about these mountains was born.

But Caleb was not merely a dull compiler of lists. Far from it. He was a highly respected mountaineer, a writer, and, perhaps most interestingly, in the light of today’s preoccupations, an early nature conservationist, concerned, for example, about the disappearance of the ospreys from their home at Loch an Eilein, in the Cairngorms.

So one theme of this unusual book is the story of the life of Caleb Cash, who emerges from its pages as an immensely likeable, very modest man, greatly appreciated by friends, colleagues, pupils and fellow mountaineers.

Interwoven with the account of Caleb’s life are MacInnes’ descriptions of his own ascents of the hills on the list which, rejecting the `Calebs’ or the `Cashs’ as names he calls The Arthurs. Reading Caleb’s List made this reviewer long to get out into the Scottish countryside so vividly are the scents, sounds and sights of the hills evoked. If, on the other hand, you don’t want the evocative stuff, merely instructions to find your way to the top of each hill, all that information is contained in a neat box at the end of each chapter (including directions to the nearest hostelry for celebrating your summit triumph).

The third theme of the book is a more philosophical one, that of the influence of wild land on the human psyche, a topic currently being explored by other writers such as Robert MacFarlane. The spur to exploring the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat and writing this book was the devastating diagnosis MacInnes, at the age of 33, received from doctors, that he had contracted the HIV virus and was suffering from AIDS related cancer. Six months of chemotherapy then radiotherapy and an on-going cocktail of anti retro viral drugs followed.

The joy in wild land which emerges in the writing of this excellent book is the joy which MacInnes experiences in his own survival and in his ability to enjoy his beloved hills. The gratitude he feels for all the support he has received is reflected in his decision that a percentage of net sales of this book will go to Waverley Care, Scotland’s leading charity supporting people living with HIV.